While working on a course in the .NET framework, I decided to take the opportunity to continue developing one of my earlier ideas: exploring how a version control system for visual design could be shaped if I designed it myself, based on my own workflow and priorities.

Traditional version control systems such as Git are extremely effective for code and text-based work. They make it easy to track changes, inspect diffs, and reason about history. In design work, versioning is often handled differently, through informal naming conventions and folder structures. This project used that contrast as a starting point, not to propose a new standard, but to reflect on how visual versioning could be supported in a small, concrete system.

There are already a few systems and asset management tools aimed at versioning visual material. This project was not an attempt to replace or compete with those tools, but rather a design experiment: to investigate which features I would choose to include, which kinds of comparison tools I would personally find useful, and how a design-first versioning workflow might look when designed from within a design practice. The focus wasn't on the UI design, but on system design and creating a tool that I would want to use.

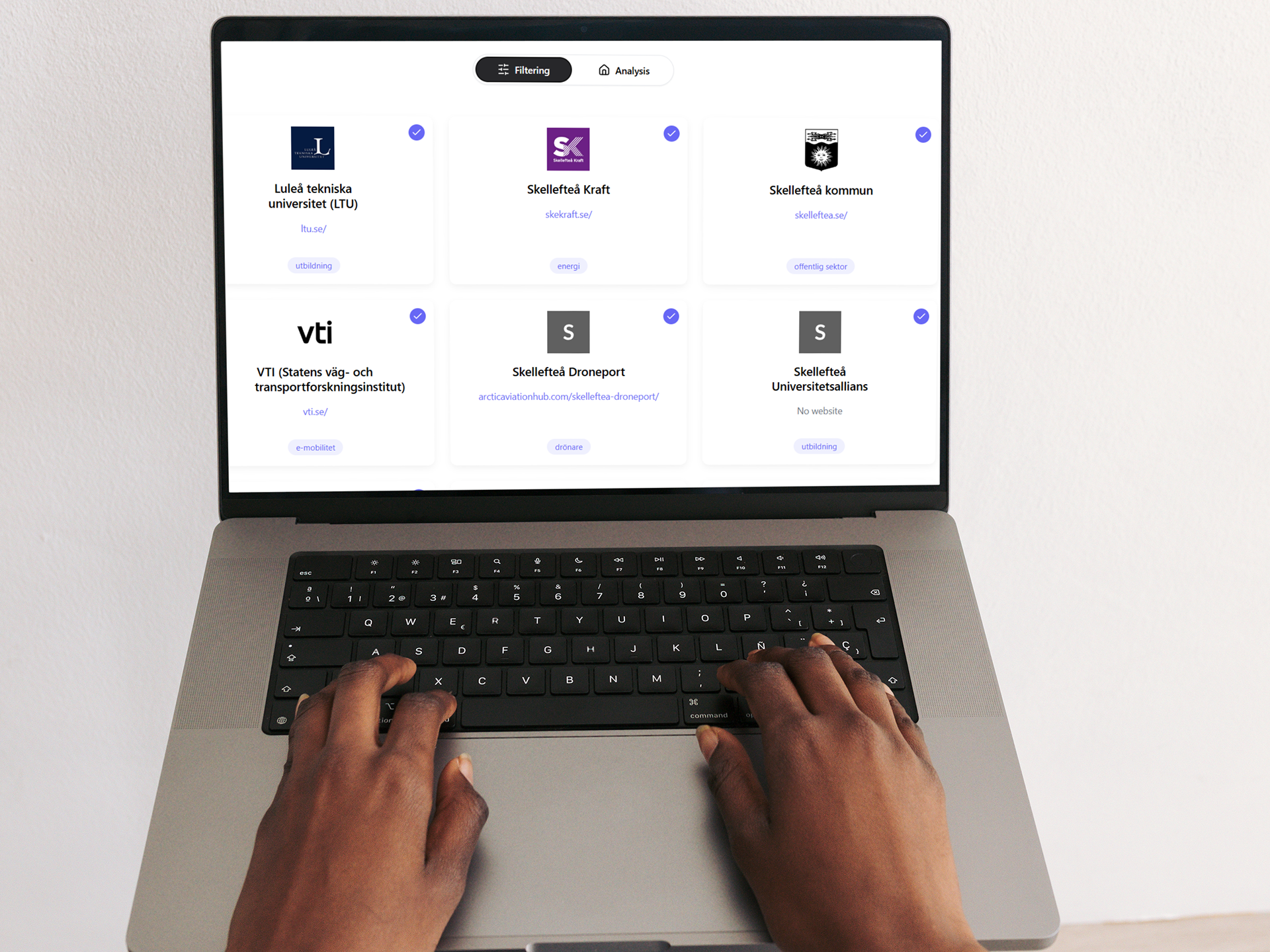

The system was built as a small ASP.NET Core MVC application with a manually implemented data access layer using ADO.NET and SQL Server. Each design project can contain multiple image versions, which can be browsed, filtered, and compared directly in the browser. Images are stored on the server, while all metadata is stored in a relational database. The technical scope was intentionally limited, in order to keep the focus on design decisions rather than on building a production-scale system.

The first comparison feature I implemented was a pixel-level diff overlay using the ImageSharp and Codeuctivity.ImageSharp.Compare libraries. This generates a difference mask between two images and overlays it on top of the original, highlighting where pixel values have changed. In practice, this turned out to be technically correct but not always perceptually useful. Even small compression artefacts produce noise, and the result can be difficult to interpret for design decisions. Rather than being a failure, this became an important observation about the limits of low-level diff techniques in a design context.

Next, I integrated a “visual weight” analysis script that I originally wrote last year while experimenting with algorithmic image analysis. This version is implemented client-side in JavaScript and uses a Sobel operator to estimate edge strength across the image. High-contrast regions are clustered and treated as masses in a simple vector field simulation, producing an overlay of arrows that point towards areas of high visual weight.

This is not intended as a realistic model of human attention, but as an exploratory tool. Compared to a raw pixel diff, this overlay provides higher-level feedback about composition, balance, and how visual emphasis shifts between versions. In the compare view, the user can switch between multiple overlay modes and fade them in and out interactively. This made it possible to directly compare how different analysis approaches support or fail to support actual design judgement.

The project was approached explicitly as a self design methodology experiment. The designer is also the primary user, and the system evolves through reflection on one’s own practice. Rather than optimizing for general usability, the focus was on which kinds of analysis genuinely support design decisions.

From a technical perspective, the project was also an exercise in building a full MVC application without relying on Entity Framework, implementing all database access manually, handling file uploads, and designing a small but coherent data model. On the client side, it became an opportunity to combine server-generated overlays with interactive canvas-based analysis.

In conclusion, this has been both a practical .NET exercise and a small design research prototype. I plan to continue using this tool myself for managing design versions and let it evolve based on real needs as they emerge. The value of the project lies less in the specific implementation, and more in the process of using system design as a way to reflect on one’s own design practice.